6. Interpreting Parity Measures¶

This lecture will follow the treatment in A Moral Framework for Understanding of Fair ML through Economic Models of Equality of Opportunity [HLG+19].

This section presents one possible translation of the parity criteria from the last lecture into the frameworks of Rawlsian Equality of Opportunity and Luck Egalitarianism. This translation is only one possible attempt at mapping these concepts and does so in an observational way. It attempts to make clear underlying assumptions of fairness in these observational criteria.

6.1. Review of Frameworks for Fairness¶

We briefly review the (quantitative) definitions for Rawlsian Equality of Opportunity and Luck Egalitarianism given in lecture 2.

Suppose that:

\(c\) stands for circumstances that capture factors beyond one’s control (e.g. circumstances of birth, or that brought on by luck).

\(e\) are actions that follow from ones choices and character (‘effort’).

\(u\) is the utility

An (allocative) policy \(\phi\) induces a distribution of utility among a population.

\(F^\phi(.|c, e)\) is the cumulative distribution of utility under policy \(\phi\), at fixed effort level \(e\) and circumstance \(c\).

Rawlsian Equality of Opportunity can be translated into the language above as follows. We say a policy \(\phi\) satisfies Rawlsian Equality of Opportunity if for all circumstances \(c,c'\) and all efffort levels \(e\),

This notion supposes a view of effort that makes sense to compare between any two individuals. Effort is inherent to an individual and not impacted by circumstance \(c\). Also recall that effort captures a lot more than simple effort (according to Rawls, it captures talent, ambition and other natural characteristics as effort).

Luck Egalitarian Equality of Opportunity can be translated into the language above as follows. Suppose that \(\pi\) is the \(\pi\)th quantile of the distribution of effort of individuals under circumstance \(c\). Then a policy satisfies Luck Egalitarian EO if for all \(\phi\in[0,1]\) and any two circumstances \(c, c'\)

In the deciding admission to college, this would be like comparing those at top 10% of their high-school class. Students at different high schools likely have different absolute academic credentials. This policy considers the environment (circumstance) the student came from when comparing effort levels.

6.2. Translating the Components of an Algorithmic Decision¶

Now we will translate the formalism above into the context of an algorithmic decision making system. Consider the notation from the previous lecture:

\(X\) are relevant attributes (e.g. those reasonable for making decisions)

\(A\) are irrelevant attributes (e.g. race)

\(Y\) is the outcome or true label.

\(\hat{Y} = C(X, A)\) is an allocation by a classifier.

The utility that an algorithmic decision imparts may be described as follows:

\(d\in[0,1]\) is an individual’s effort-based utility. This is the utility they receive based on relevant factors made by the individual. This utility is not directly observable.

\(a\in[0,1]\) is the actual utility the individual receives subsequent to receiving allocation \(\hat{y}\).

\(u\) is the utility or advantage the individual earns as a result of being subject to the decision \(C\). We assume \(u = a - d\) in these notes.

The overall utility \(u\) is what you want to equalize across individuals in similar circumstances. Note:

If \(u = 0\), then \(a = d\) and effort directly matches what’s given.

If \(u >0\), then \(a > d\) and the individual benefits from the decision (beyond effort).

If \(u<0\), then \(a < d\) and the individual is harmed by the decision (taking effort into account).

Equality of Opportunity, according to Heidari et al., requires individuals with similar effort have similar prospects of earning the advantage \(u\). How similarity of effort is measured changes the specific conception of EO.

We can translate our formalism about EO into the language of machine learning:

Eqality of Opportunity |

Machine Learning |

|---|---|

policy \(\phi\) |

classifier \(C\) |

effort \(e\) |

effort-based utility \(d\) |

circumstance \(c\) |

irrelevant attributes \(A\) |

utility \(u\) |

overall utility $u = (a - d) |

Note: by capturing circumstance with \(A\), we are simplifying an individual notion of fairness to one about groups.

6.2.1. Rawlsian FEO¶

Rawlsian EO requires effort \(d\) to not be affected by irrelevant features \(A\) and the specific decision \(C\). Let \(F^C(.)\) be the distribution of utility \(u\) across individuals under the allocative decisions made by \(C\). The Rawlsian EOP translates to:

That is, for fixed effort \(d\), the distribution of utility does not depend on circumstance \(A\).

Many of the parity criteria from the last lecture are naturally described using Rawlsian Fair Equality of Opportunity, for different choices of effort. This allows us to clearly describe the assumptions we make when requiring a specific parity measure to hold.

Equality of Odds. If the true binary label \(Y\) reflects an individual’s effort-based utility \(D\), then Rawlsian FEO translates to equality of odds across protected groups. That is:

\(d = Y\)

\(a = \hat{Y}\)

$u = (Y - \hat{Y})

That is, equality of odds is a world where you receive exactly what you work for. Practically speaking however, if the true label identified in the training data doesn’t perfectly reflect a persons effort, this condition no longer holds!

Demographic Parity is framed as Rawlsian EO by defining the effort-based utility as constant of \(d = 1\) and the actual utility to be the result of the decision \(a = \hat{Y}\). This implies that each person has some intrinsic constant utility that’s independent of effort or circumstances. Such an assignment may be reasonable if you are considering the distribution of a good that equally deserved among all people (e.g. an inalienable right).

Accuracy Parity is framed as Rawlsian EO by defining the effort-based utility as constant of \(d = 0\) and the actual utility to be the discrepancy between the decision and the true label \((\hat{Y} - Y)^2\). This implies that individual has no intrinsic utility and all that matters is the correctness of the outcome.

The proofs of these equivalences are found in [HLG+19].

6.2.2. Luck Egalitarianism¶

With notation as before, define \(\pi\) to be the distribution of utility for individuals in at the \(\pi\)th quantile of the distribution of effort-based utility. Equalizing opportunities means choosing the predictive model \(C\) to equalize the distribution of utility across types, at fixed levels of \(\pi\):

Predictive Value Parity is framed as Luck Egalitarianism, by equating effort-based utility with the classifiers decision \(d = \hat{Y}\) and actual utility with the true outcome \(a = Y\).

Here, the assumption made is that “differences in actual outcomes among equally risky individuals is mainly driven by arbitrary factors, such as brute luck” [HLG+19]. Thus predictive value parity assumes that the classifier’s assessment is assumed to capture effort, while differences between effort in the actual outcome are primarily due to circumstance.

Remark: Predictive Value Parity cannot be framed as Rawlsian, as it requires conditioning on the decisions made by the classifier; it requires equal rates of true outcomes across similar predictions.

Different choices of \(d\) and \(a\) may lead to new parity measures that encode different values. [HLG+19] explores some of these at the end of the paper.

6.3. Interpretations of trade-off using Equality of Opportunity¶

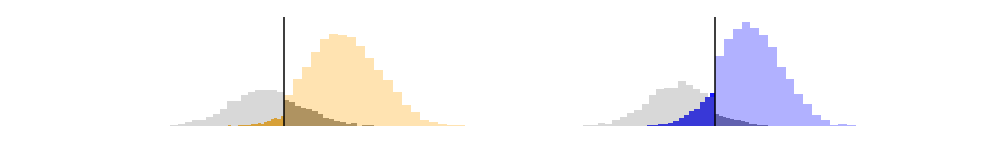

Predictive value parity and equality of odds cannot hold simultaneously due to differences in moral assumptions encoded in effort-based utility \(d\):

Equality of odds assumes persons with similar true labels are equally accountable for their labels.

Predictive value parity assumes all persons with the same ‘risk’ (predicted label) are equally accountable for their predictions.